Do you find yourself dashing through challenges with finesse as a speedrunner? Or perhaps you enjoy savoring the meticulous journey as a completionist, leaving no stone unturned? For the last couple of gaming generations, there has been a serious competition between these two conflicting ideals.

Speedrunners have been around for a while but the rise of Twitch and livestreaming has turned speedrunning truly into a spectator sport. Players are ranked on centralized sites such as speedrun.com, to show who is indisputably the best in a given category. This competition to be the best can become distracting. The games lose their artistic appeal and are reduced to consumer products. Only the player and their skill matters, so they will clear one run and move onto the next. It brings absurdity as the limits of human capability are often thrown off by chance and runners practically gamble for “lucky runs”. At a high enough level, further competition becomes pointless.

Recommended Viewing: The Absurdity of Speedrunning by OtherRuns.

On the other hand we have the completionists. The completionist playstyle has come into prominence through Twitter, personas such as the titular Completionist and through detailed completion guides earlier on Something Awful and GameFAQs. Where speedrunners are obsessed with rankings, completionists fixate on achievements and percentage scores. It is not so much about being the better player for a completionist, but experiencing all a game has to offer. Nonetheless, too much completionism can also devolve into something absurd as we obsess over minutia. It brings anxiety that the player must see everything and do everything.

Recommended Viewing: You Don’t Need To Finish Games by GC Vazquez

In the minds of many people these playstyles are mutually exclusive. So the debate, as I have experienced it, has been on whether it is “better” to play with a speedrunner mindset or a completionist mindset. I think that a very good answer to this question was given a long time ago, but not many people have heard about it. It’s a little game called Cave Story.

Dōkutsu Monogatari, or Cave Story, is a genre defining metroidvania. It is an indie game developed between 1999-2004 and was originally released as shareware. Cave Story is highly acclaimed and it inspired a whole generation of indie games and eventually received a few console releases.

Is it still worth playing in 2023? Yes, yes, yes!

Cave Story does many good things, but I want to focus on how it handles contrast. You will always find opposites working together in this game; nature and technology, light and darkness, safety and peril. Indeed the game contains thematic contrast but this is also complemented by mechanical contrast. Many mechanics in the game are designed to challenge speedrunners, yet many others are designed to reward completionists. This contrast in mechanics makes Cave Story the perfect game to explore game design which both appeals to an audience of speedrunners and completionists and ask how it through this mix of playstyles makes an argument for what speedrunning could be.

Reflexes

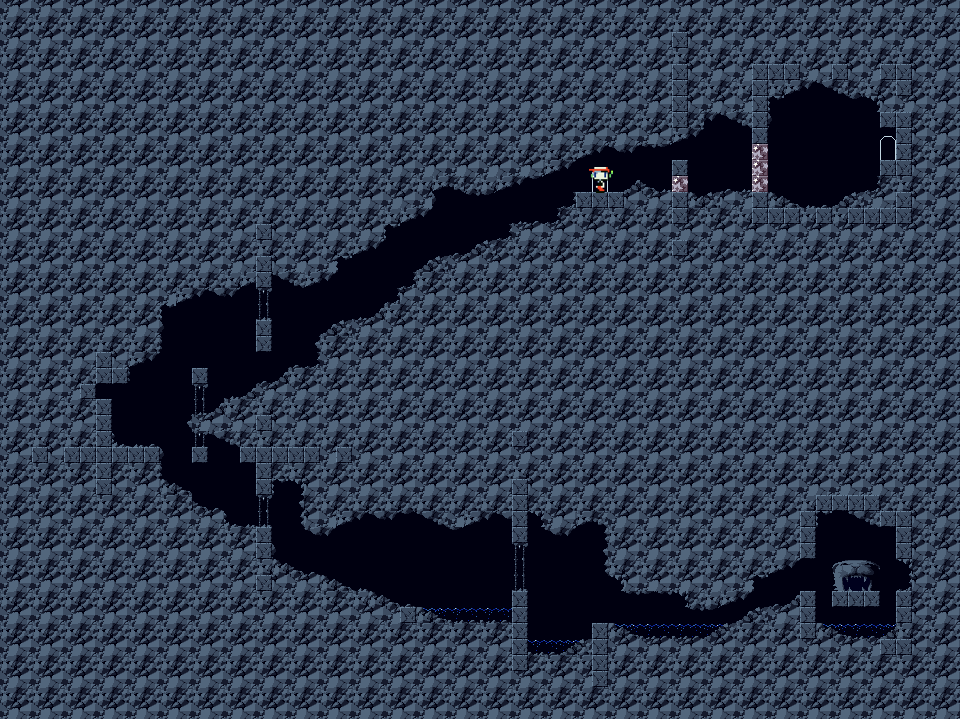

One of the first screens the player encounters in the game is this above area simply called “The First Cave”. Unlike in most metroidvanias, our hero, the robot Quote, starts without any weapons. So the player does not have any way to defend themself or affect the environment. The player is faced with an illusion of choice: although the path branches left and right, there is no way to cross to the right because of a wall. The player can walk up enough to see the space behind the wall, even if they cannot pass it. Instinctively, The player is forced to pick the left.

The level railroads us into a round-about path full of monsters, bats, spikes, water and other hazards we can only jump past. The player is given no choice but to explore, so in this phase of the game exploration is the only form of progression. You can try to explore faster to find safety, or do it slowly to understand the behavior of the different hazards. At the end of the long path lies a proverbial lion’s maw to warn the player “it only gets more difficult from here”.

In there the player finds nothing more than a gun. You must then exit out of the lion’s mouth, and once more follow the path backwards. Only this time the player is able to power through the area with ease. Bringing us to the right path from before.

The off-color wall is vulnerable to your projectiles. Instinct tells the player to go open the door. But it’s booby trapped. If the player falls into the trap of running around mindlessly thinking “I have a gun now, I am invincible” they will take damage.

The first lesson here to learn from Cave Story is that as a game designer, you have the ability to play with the player’s reflexes. A savvy designer can signal a player whether they are rushing too much or exploring for too long. If you want the player to pay attention to their surroundings, disarm them. If you want the player to not dawdle along, hit them with a time limit and moving objects (as happens later in the game). Designer action translates to player reaction. It can only help to talk to your player. Which brings us to the next point.

Sequence Breaking

One of the most iconic moments in the game comes in the area called the Plantation. Secrets are revealed, the situation is grim and the stakes could not get any higher. The player must work through a fetch quest to help a pair of scientists build a rocket to propel Quote out of the Cave™ to the surface.

But what if the player could skip it? In the original release of Cave Story such a skip was possible.

But there’s a catch, the door won’t let the player pass! Pixel, the developer, either knew the skip was possible or suspected that someone might find a way. So if the player tries to play their own way, skipping not only the area but also the story, Pixel says “I don’t think so”. This is one of several checkpoints where players who have been running too fast are demanded to come back once they have done something and triggered a flag.

Developer foresight like this can be pretty cool and not all developers deny player skips in this way. For example, if the player skips certain upgrades in Super Paper Mario the player is given them at the end of a level so they don’t end up soft-locking themselves later on. On the other hand, Cave Story has a more hostile relationship with the player. The more a player tries to ignore the story of the game, the more ways the game will find to punish them. Worse endings and missable items are one thing. But these progress checkpoints serve as the icing on the cake. If the player ignores the story, the game will ignore their progress.

Cave Story rejects sequence breaking, it just is not allowed. The player must rise to the occasion and complete the fetch quest before the locked door opens. Once the story is told and the flags set, the player is free to perform the area skip instead of riding the rocket. This has been demonstrated in nitsuja’s former world record (TSA 50:10.30) 42 minutes into the run.

Thus comes our second lesson from Cave Story: The player and designer ought to negotiate sequence breaks. As a player, you are welcome to defy the game’s design, but you must always respect it. You can break what you don’t understand, but you cannot reverse engineer it without understanding. As a designer, you cannot ignore that players might want to do things out of order. The worst thing you can do is keep quiet. Rather, it is better for the designer to congratulate or berate a player who has succeeded in doing things differently. Only when the designer and player acknowledge one another do we get something perfect where the designer can tell the story they want to and the player can play as they want to.

Becoming a Completionist Speedrunner

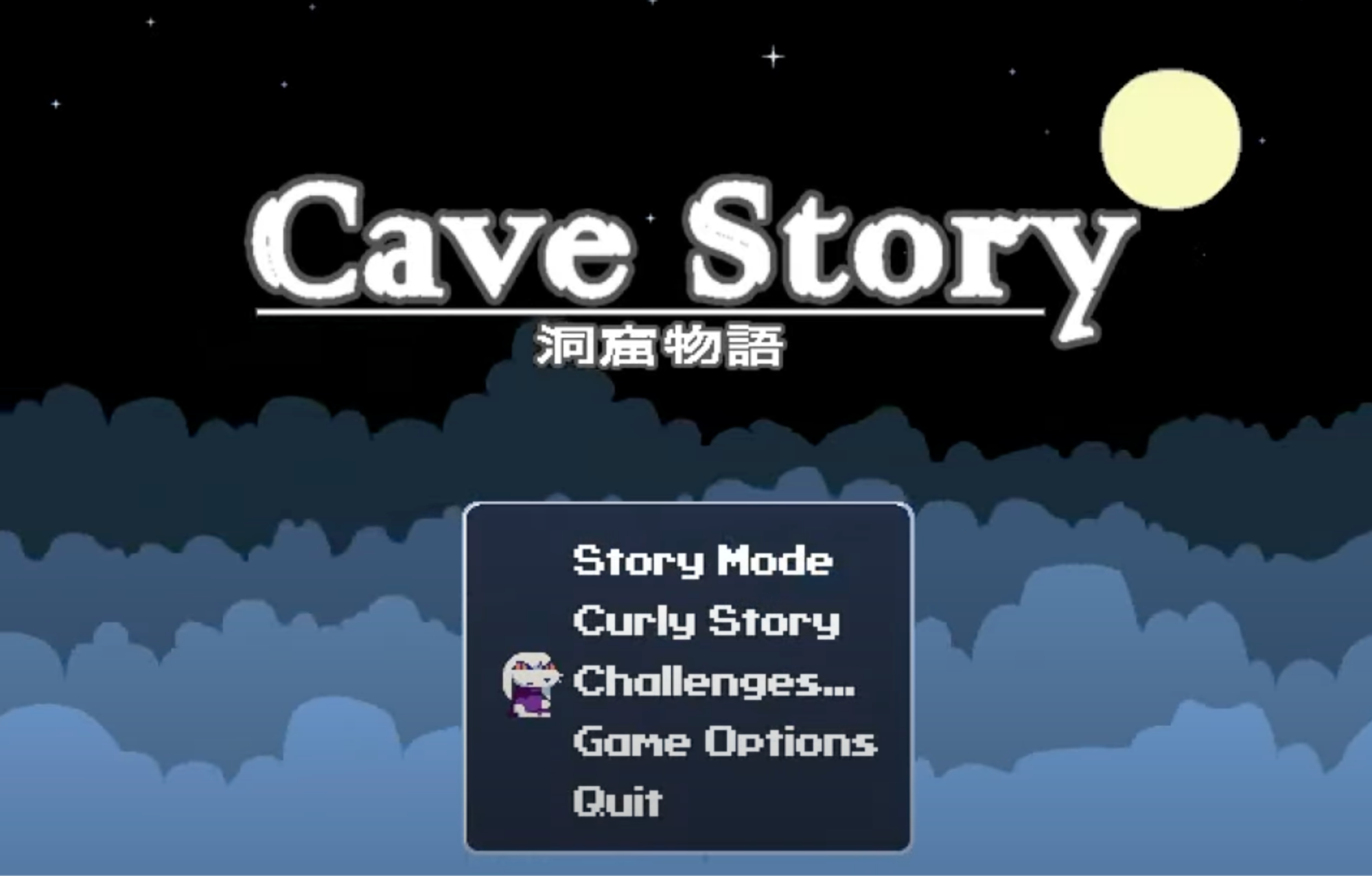

The Secret Good Ending of Cave Story will lead you down a rabbit hole. If the player is on the path to the coveted secret ending, they will eventually obtain a hidden chronometer. Surely, the speedrunners have been waiting for this moment! But it appears to be a dud, seeing as they cannot even start it.

Only when the player thinks that they have finished the game and wind up in the dreaded Blood Stained Sanctuary, that is when the chronometer will activate and start counting. Welcome to Hell!

In addition to having instant death traps, killer music and a bunch of new mechanics; the true final level of the game also tracks how long the player takes to complete it. This is the one part of the game where the game is actively cheering the player on as they run past everything. Though the game will not hesitate to throw every possible danger the player’s way. Blood Stained Sanctuary is hard and very much there as a challenge for skilled players.

After many failed attempts, game over jingles and cheap deaths, the player has finally beaten the true final boss and saved the world! Congratulations! In most games, this would be the true end™. But of course, Cave Story goes the extra mile.

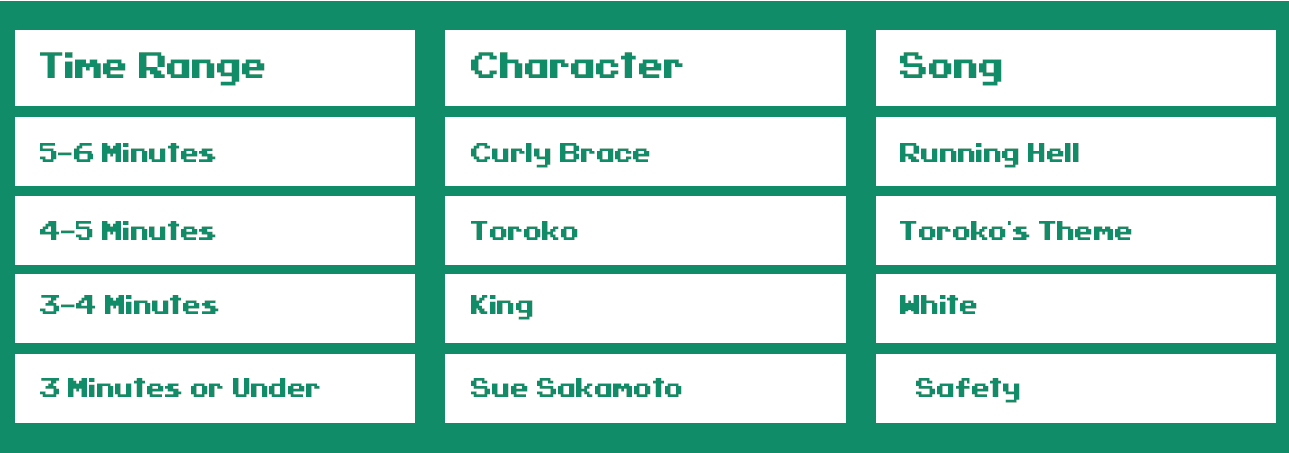

That clock in the corner was not just for show; the title screen will change based on how long it took the player to clear the Blood Stained Sanctuary. If the player can clear the level in under 6 minutes, they will receive a new character on the title screen and a different song will play. To my knowledge, this mechanic has been kept intact in all ports of the game, and is probably easier on newer releases which let the player instantly jump to the Blood Stained Sanctuary in the post-game.

Of the four characters / songs that the player can unlock in this way, two of them are unused songs never heard during gameplay. In a way, to truly “complete” the game the player must “run” through the Blood Stained sanctuary a few times. Below is a table for what time ranges are needed for unlocking.

This is brilliant. Instead of giving the player a gold or silver medal (looking at you Donkey Country Returns) each completion time has its own unique reward. If the player has been playing the entire game, taking their time and trying to explore as much as they could; now begins the grind where they will have to run to complete the game. And if the player is skilled enough and feels that the game wasn’t challenging enough, here is their big challenge! I don’t think it’s possible for anyone to run BSS in their first run in under 3 minutes, so a player who is going to run through BSS repeatedly will most likely fill all 4 brackets in subsequent runs.

That is the third and final lesson we can learn from Cave Story: Unique rewards can make all the difference. If these unlocks were treated like rankings or had different utility, people would immediately rush for the <3 minute category, to prove themselves “the best”. But in having hidden different rewards for different runs, there is an added appeal of curiosity in trying to get a run in all four brackets. As a player discovering that the title screen changes when you run in under 6 minutes for the first time you are compelled to try better next time to see if the song will change again. The player can define what is progression for themselves, instead of having the game snarkily tell you “there’s a shinier reward if you can run faster” or the community calling you “subpar”.

Discussion: Mocking the player

Cave Story is certainly not the only game to have openly mocked players for investing in either a speedrunner mindset or a completionist mindset, but it was one of the first. A more popular game that criticizes this duality has been Undertale. The player is judged directly in the Last Corridor for all the carnage they have caused while running around haphazardly hurting and killing the monsters. A completionist who avoids violence at first but then is seduced to attempt the infamous Genocide Route is also in a similar way mocked for their bizarre obsession with the game. Just because you have the ability to do something, should you do it? Is it worth it? Is, for example, killing every single monster in the game an objective you want to proclaim yourself to be the best in? Or, instead, wouldn’t you consider getting the happy ending as fast as possible?

A lesser known title is Chaos;Head from 2008. Though only remembered today as the prequel to Steins;Gate, Chaos;Head is a game full of commentary on Japanese politics, the tropes and attitudes dominating the game industry and the deterioration within the gaming scene and its subcultures. If you are not paying attention to the game fast-forwarding through everything, bam! You get a bad ending. But maybe you’re curious about the recurring Whose Eyes are Those Eyes message and are constantly reloading to make sure you trigger the correct flag for every possible “Whose Eyes are Those Eyes” message in the game. Well, your reward for being so curious is that you get to learn all about the serial killings and whodunnit at the cost that you get the absolute worst ending possible, you filthy cheater! The path to the true ending (in the original PC release, not Steam) required you to play through the entire game, pay attention to the story and solve the Yes/No puzzle at the end correctly. So your one way to get the good ending was to follow the story. Do it as fast or complete as you want, you can branch off into various dialogue just fine, but you must acknowledge the game and its world if you want to get to the good ending. You have to earn it.

Both Undertale and Chaos;Head have been rebuked for being retro or even outdated, sometimes in direct reaction to their commentary on players and playstyles. Here, what makes Cave Story so fascinating is that it is very subtle in how it criticizes players. The commentary on playstyles is embedded into the game mechanics and so it did not require the designer to subvert their genre to get the message across. Whether you are a completionist or a speedrunner you will come out of Cave Story having had fun, because what you have here is an unconventional game but not an unfamiliar one. Today’s Celeste players or the older gen of Megaman players will find themselves right at home.

Conclusion

I think that the thesis Cave Story presents is that instead of some split between speedrunning/completing (or exploitation/exploration), it is more meaningful to think about how you do the correct thing, the fastest. Rather than having the player set arbitrary challenges for themself, it introduces dilemmas and conflicts that the player has to answer as they play through the game. Cave Story is a game that is not afraid to tell the player “you are doing something wrong” when the player tries to break away from the world and its characters in the name of getting things done quickly. Cave Story hands the player challenges and asks “how fast can you complete my challenge?”, entering into a dialogue with the player as it refuses to be just another title to be forgotten amidst the hype for only the newest games on Twitch and other gaming communities. It emerges as something truly memorable which certainly makes the game relevant for today’s players and designers despite its almost 20 years of age.